Tags

civility, codes of conduct, historical reenactors, personal, philosophy, progressive reenacting, Sharon Burnston

These have been a tough couple of years. We are, once again it seems, in a period of polarization and increasing political violence. In times like these, when disagreements flare brighter and behavioural norms are changing, even the things we do for fun can be affected. From online fights that turn nastier than ever to onsite behaviour that runs the gamut from passive-aggressive to hostile, the real world creeps into our fantasy worlds. I have experienced and seen behaviour that I find unacceptable. It was subtle, but not acceptable. When I posted about it online, a lively discussion ensued.

These have been a tough couple of years. We are, once again it seems, in a period of polarization and increasing political violence. In times like these, when disagreements flare brighter and behavioural norms are changing, even the things we do for fun can be affected. From online fights that turn nastier than ever to onsite behaviour that runs the gamut from passive-aggressive to hostile, the real world creeps into our fantasy worlds. I have experienced and seen behaviour that I find unacceptable. It was subtle, but not acceptable. When I posted about it online, a lively discussion ensued.

From that, an idea was born: Sharon Burnston suggested a Code of Conduct, which I heartily endorsed. Drawing on her experience organizing and managing events and groups, Sharon wrote a draft code of conduct. Now, with edits and suggestions from others, it is available on her website.

“We are all here at this site/event for the same purpose, to portray events that happened here in the past for the benefit of the public, and for our own enjoyment. We agree to follow the site’s rules for fire safety, gunpowder and weapon safety, curfew, alcohol consumption, and whatever other restrictions they require of reenactors. Just as we have agreed to adhere to standards for our clothing and our kit, it is appropriate that we agree to adhere to standards for our behavior. The standards for our behavior are modern, not period. We are interpreting history, not re-creating historical attitudes to class, gender, or race. We are 21st century people, and 21st century expectations apply.

In its simplest terms, treat everyone else as you would want them to treat you. Don’t be a jerk. But to break it down into specifics, and in order for this community to feel welcoming to the largest possible population, we expect everyone to endorse the following standards of behavior. Anyone who cannot adhere to these simple rules will not be invited to future events.”

Don’t be a jerk.

Seems so simple, right? Apparently not for everyone, because not everyone embraced a fundamental grade-school lesson:

“I will take responsibility for both my actions and my feelings. I have the right to have my feelings respected, I have the right to be heard and understood, I have the right not to feel pressured or browbeaten. I extend the same rights to all other reenactors and to the public.”

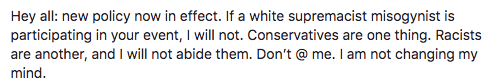

For me, this presents an interesting conundrum. You see, I kinda started this when I announced online:

Now, this is in fact a wimpy way to deal with a person who I think treated me pretty shabbily at an event, and who made clearly misogynistic comments at that event, and has posted white nationalist stuff on social media. A quicker-witted person than I would follow Sharon’s precept six:

“I will call out these inappropriate behaviors in others. If I see something, I will say something – either to the offender directly or to an authority figure – a captain, event planner/organizer, or someone I trust. I will stand in solidarity with my fellow reenactors and pledge to stand up to bullies, abusers, and other unpleasant behavior to ensure the safety and comfort of those around me.”

This last is easier for some than for others. It gets easier when one can believe that one will be listened to, heard, and taken seriously. And that is not on the person reporting: that’s on the person hearing. When someone’s feelings are dismissed, or another’s actions excused (he’s a good guy; he’s just insecure), the status quo is maintained, the ranks secured, and the world unchanged. It will take all of us to make places safe and pleasant to be it. A code of conduct we can all agree to is a good place to start.