Tags

18th century, britishareback, Occupied Philadelphia, Philadelphia, women's history, women's work

Part three of a series

So what did Elizabeth Weed prepare and sell? What remedies were used and preferred in 1777 Philadelphia? And where to look?

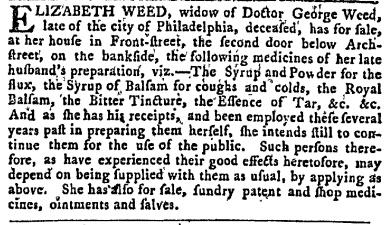

The ad is explicit: “The Syrup and Power for the flux, the Syrup of Balsam for coughs and colds, the Royal Balsam, the Bitter Tincture, the Essence of Tar, etc.”

Margaret Hill Morris used William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine as one of her references, but receipts for cures can be found in The Compleat English Housewife, and Hannah Glasse as well. I’ve held a fascination with tooth cleaning and hygiene for some time, so this project was a natural outgrowth of those interests.

Fortunately, ingredients were pretty easy to come by (many already in my kitchen), and a sacrificial pan had been created making wax blocks for sewing kits. We started experiments in earnest October 6th, after coming home from the Draken Harald Harfårge. We did not fully anticipate how much one of the decoctions would smell like the Draken.

Tar Water was particularly intriguing, since it had been prescribed to John Francis, son of Ann Willing Francis (and eventual husband of Abigail Brown). Francis suffered from poor health, and he and his wife, and mother, all recorded the use of “tar water” in diaries and letters. Eventually I found a receipt that cured me of the notion of drinking tar itself: Tar, two pounds; water, one gallon. After standing to settle for two days, pour off the water for use.

Well, there it is: water infused with essence of tar, which turns out to be “best Norway Tar,” or pine tar. Decanted, it smells like ships’ ropes coated to protect them from sea water.

So there are recipes to follow (even some of Elizabeth Weed’s own, recorded in the back of Thomas Nevell’s day book); but what does a shop look like? What bottles, pots, jars, and labels are used? The backgrounds of satirical engravings provide some guidance (and some hilarity).

In the background of the print at left, we can see some of the furniture and equipment of the pharmacists’ trade. Wooden pharmacy chests with drawers for ingredients; glass bottles above, with round-topped stoppers; above that, ovoid storage jars, possibly Delftware, for the storage of additional dry materials. A large mortar and pestle sits on the counter in front of the drawers.

Smaller, labeled bottles sit on the table of the Village Doctress, along with an ointment pot (gallipot), as well as scissors and an hourglass. These similar, but simpler, tools help us recognize the lower status of the “doctress” relative to male doctors (as do the way she’s depicted, hunched over her patient, in lappet cap and black neck handkerchief or mantelet, placing her as widowed and aged). With the inheritance of her late husband’s medicines and goods, where does Elizabeth Weed fit between the doctor and the doctress? While it is impossible to say with certainly, it’s likely her material surroundings, and the equipment she had to use, was closer to the well-kitted pharmacy of the “Quaker doctor” print than to the “Village Doctress.”